The cost of South Africa’s misguided AIDS policies

[ Spring 2009 ]

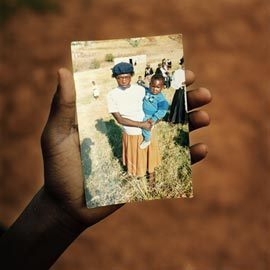

The human cost of South Africa’s misguided AIDS policies

AIDS activists and researchers argued for years that the negligent HIV/AIDS policies of former South African President Thabo Mbeki were causing a massive, unconscionable loss of human life. Now, thanks to the doctoral thesis of a student at the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH), they know the full extent of the damage.

More than 330,000 people died prematurely from HIV/AIDS between 2000 and 2005 due to the Mbeki government’s obstruction of life-saving treatment, and at least 35,000 babies were born with HIV infections that could have been prevented.

These estimates appeared online in October in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome in a study by HSPH’s Pride Chigwedere, who graduated with a doctor of science in immunology and infectious diseases in June of 2008. Chigwedere laid South Africa’s heavy toll from HIV at the feet of Mbeki, who delayed launching an antiretroviral (ARV) drug program, charging that the drugs were toxic and an effort by the West to weaken his country. Mbeki withdrew government support from clinics that had started using AZT to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. He also restricted the use of a pharmaceutical company’s donated supply of nevirapine, another drug that helps keep newborns from contracting HIV.

These estimates appeared online in October in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome in a study by HSPH’s Pride Chigwedere, who graduated with a doctor of science in immunology and infectious diseases in June of 2008. Chigwedere laid South Africa’s heavy toll from HIV at the feet of Mbeki, who delayed launching an antiretroviral (ARV) drug program, charging that the drugs were toxic and an effort by the West to weaken his country. Mbeki withdrew government support from clinics that had started using AZT to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. He also restricted the use of a pharmaceutical company’s donated supply of nevirapine, another drug that helps keep newborns from contracting HIV.

A DOCTOR’S SUSPICIONS

Chigwedere, a physician, came to HSPH in 2000 from Zimbabwe, where he had watched his AIDS patients die because no ARVs were available. For two years, he worked on an AIDS vaccine design as a research fellow with Max Essex, the Mary Woodard Lasker Professor of Health Sciences and head of the HSPH AIDS Initiative. After enrolling as a doctoral student, Chigwedere shifted his attention to working on ARV drugs. Initially he focused on drug resistance. This led him to look more deeply into why the drugs were not widely available in Africa.

Some countries’ track records suggested policies that were “inappropriate or frankly wrong,” says Chigwedere. Chief among the transgressors was South Africa.

Even as the country’s neighbors ramped up prevention and treatment efforts, Mbeki — president from 1999 until he resigned under pressure last September — publicly challenged the scientific consensus that HIV causes AIDS. His health minister, Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, promoted herbal remedies, including beetroot, garlic, and lemon, as alternatives for ARVs. Such policies condemned thousands to die, Chigwedere says. But could their impact be measured?

CALCULATING LOSSES

Under relentless pressure from the Treatment Action Campaign, an activist group, South Africa finally launched a program in 2003 to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV and a national ARV program the following year. Still, by 2005, report Chigwedere and his colleagues, only 23 percent of AIDS patients were on life-saving drugs, and fewer than 30 percent of pregnant, HIV-infected women were receiving nevirapine. By comparison, Botswana and Namibia were treating more than 70 percent of patients.

To put Mbeki’s failings into terms the world could understand, Chigwedere estimated the number of deaths caused by delaying and restricting ARV use. He compared the number of South Africans on ARVs between 2000 and 2005 with the number the country might reasonably have treated, based on the performances of neighboring countries. Factoring in the drugs’ effectiveness rate, Chigwedere calculated the total years of life lost.

Commenting on the study’s methodology in the New York Times, James Chin, a professor of epidemiology at the University of California at Berkeley’s School of Public Health, called the numbers “conservative” and “quite reasonable.” The study hit page one of the paper on November 26, 2008, and the front pages of the International Herald Tribune and the Times of South Africa. The BBC, Al Jazeera, Fox News, and other media outlets picked up the story. Chigwedere, who now works with global health care companies at McKinsey and Company, a management consulting firm, is still giving interviews.

“The response has been beyond our wildest dreams,” he says.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Mbeki refuses to comment on the paper but does not deny its findings. He is serving as a regionally appointed mediator in Zimbabwe’s political crisis.

“Ashamed” was the reaction of South Africa’s new health minister, Barbara Hogan. A longtime Mbeki critic, Hogan took office the same day as Mbeki’s interim successor, Kgalema Motlanthe. Hogan has made HIV/AIDS a priority, mobilizing the public through a new prevention campaign and brokering a $22 million donation from the British government to help cover ARV costs. Tshabalala-Msimang’s role is diminished in the new administration.

Treatment Action Campaign leader Zackie Achmat called for Mbeki and Tshabalala-Msimang to be tried by a judicial board similar to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which rendered judgment on apartheid-era abuses.

Chigwedere’s next paper will look broadly at how governments might be held accountable for their public health policies. “Once it’s been determined whether a policy is beneficial or harmful, that leads to the discussion of public health malpractice,” Chigwedere says. “How do we develop standards in public health? This is a whole new area opening up.”

Amy Roeder is the development communications coordinator in the Office for Resource Development at HSPH; Photo, top left, Chris de Bode/PANOS; top right, courtesy of Pride Chigwedere